Can activists claim right to privacy?

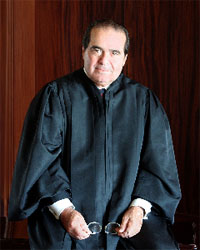

Antonin Scalia

For the second time this month, the U.S. Supreme Court’s most conservative member, Justice Antonin Scalia, on Wednesday took a surprising position—one that is helpful to gay civil rights.

“The First Amendment,” said Scalia during oral arguments in a case involving the 2008 Washington State referendum on a domestic partnership law, “does not protect you from criticism or even nasty phone calls when you exercise your political rights to legislate, or to take part in the legislative process.” The point was essentially the same as that made by five national gay legal and political groups in their friend-of-the-court brief in the case, Doe v. Reed.

Earlier this month, in an oral argument about the First Amendment right of a religious student group to ignore a campus policy prohibiting sexual orientation discrimination, Scalia chastised the religious student group. He said the Christian Legal Society had not introduced any evidence to prove it was being treated differently from other campus groups under the University of California’s non-discrimination policy.

Scalia’s remarks in two oral arguments do not constitute a turnaround for the justice; but his remarks in the Doe v. Reed discourse seemed to strongly suggest he would vote against the anti-gay group Protect Marriage Washington, which brought the case.

In fact, only two justices—Chief Justice John Roberts and Justice Sam Alito—appeared to offer Protect Marriage any hope of support Wednesday.

During Wednesday’s oral argument, former Mitt Romney presidential campaign adviser James Bopp, representing Protect Marriage Washington and two “John Doe” plaintiffs, argued that the “First Amendment protects citizens from intimidation resulting from compelled disclosure of their identity and beliefs and their private associations.”

Specifically, Bopp and his clients challenged the constitutionality of a Washington State law that makes public the names and addresses of citizens who sign petitions to put various issues onto the ballot. They said the public disclosure of the identities of petition signers had a chilling effect on their freedom of speech because they feared reprisals and harassment from citizens who didn’t agree with them. And, they said, it violated their right to privacy. A federal district court judge in Seattle had agreed with them but the 9th Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals did not, so they appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Although the facts of this particular case revolved around a dispute over a domestic partnership law as well as, indirectly, California’s Proposition 8, the justices wrestled with the implications of Protect Marriage’s argument for a wide scope of matters.

In fact, Bopp had barely gotten his first sentence out when Scalia launched his inquiry, wanting to know whether Bopp’s logic would extend to laws requiring disclosures of campaign contributions. Justice Sonia Sotomayor jumped in, saying Bopp’s theory “would invalidate all of the state laws that require disclosure of voter registration lists.” Justice Anthony Kennedy suggested Bopp’s argument would seem to make illegal boycotts of businesses that support a referendum.

Bopp said no, and tried to contend that his legal challenge to the Washington State Public Records Act concerned its application only to referenda petitions. But Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg asked why, then, his argument wouldn’t cover a campaign contributor who worried about being harassed over the candidate he or she chose to fund. And why, asked Ginsburg, was Protect Marriage trying to protect the privacy of petition signers through public documents at the same time it was selling those names to other organizations for fundraising purposes.

Bopp tried to point to earlier Supreme Court decisions for help. For instance, he cited a 1999 decision, Buckley v. American Constitutional Law Foundation, led by Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, that struck down a Colorado law that required people circulating petitions to be registered voters, wear an identification badge with their names on them, and their names and addresses on each petition. In an 8 to 1 decision, the court ruled that the law violated the First Amendment right to free speech. Then-Chief Justice William Rehnquist was the lone dissent.

Scalia rebuffed Bopp’s attempt, saying there was a qualitative difference between collecting signatures on a petition and signing the petition. The latter, he said, was participating in a legislative act.

“The fact is,” said Scalia, “that running a democracy takes a certain amount of civic courage. And the First Amendment does not protect you from criticism or even nasty phone calls when you exercise your political rights to legislate, or to take part in the legislative process.”

Later, Scalia elaborated, saying, “The people of Washington evidently think that [the public disclosure law] is not too much of an imposition upon people’s courage, to stand up and sign something and be willing to stand behind it.”

It was at this point that Chief Justice John Roberts jumped in with a defense of Bopp’s position by using a sort of reverse discrimination argument, saying, “One of the purposes of the First Amendment is to protect minorities.”

But Scalia seemed convinced the disclosure is a reasonable safeguard in a democracy.

“Threats should be moved against vigorously,” said Scalia, “but just because there can be criminal activity doesn’t mean that you have to eliminate a procedure that is otherwise perfectly reasonable.” It was an argument similar to one made by the gay brief.

The gay brief states that ballot measures, such as Referendum 71, lead to increased harassment and violence against LGBT people, not petition signers. It said proponents of Referendum 71 did not produce facts to support their claims that petition signers had been subject to any systematic harassment or intimidation. And it said Protect Marriage’s claims that petition signers were being harassed was just another political tactic by the anti-gay activists both in Washington and in California.

“When subjecting a minority group to political attack, a common tactic is to claim that the minority is itself the aggressor from whom protection is required,” stated the gay brief.

The gay brief was filed by Lambda Legal Defense and Education Fund, Gay and Lesbian Advocates and Defenders, and the National Center for Lesbian Rights, along with the Human Rights Campaign and the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force.

Washington State Attorney General Robert McKenna mentioned the “Lambda brief” during his time before the court Wednesday. He noted the brief detailed how a similar public disclosure law in Massachusetts had enabled “more than 2,000” citizens to discover and report that their signatures had been improperly attributed to a petition seeking a ballot measure to repeal a marriage equality law in that state in 2006.

The Lambda brief said that keeping petition signatures as part of the public record provides a “much needed procedural check” on initiatives seeking to take away rights of minorities and that it helps prevent fraud in election.

According to Justice Ginsburg, about 20 states have laws similar to Washington State requiring public disclosure of petition signers for ballot measures.

Roberts, Alito, and Justice Stephen Breyer all asked questions of McKenna seeking his concession that public disclosure laws could have a chilling effect on a signer’s willingness to exercise his First Amendment rights. They focused on reports that certain groups—such as knowtheyneighbor.org—were posting petition signers’ names and addresses on their Internet websites to encourage LGBT people to talk to them about the issue.

“Suppose that, in 1957 in Little Rock, a group of Little Rock citizens had wanted to put on the ballot a petition to require the school board to reopen Central High School, which had been closed because there was a sentiment in the community that they didn’t want integration,” said Breyer. Mobs of white people opposed to integration employed violent tactics to keep blacks out of the school, forcing then President Eisenhower to call in federal troops to enforce the historic Brown v. Board decision to desegregate.

What if people who supported integration, said Breyer, knew that “if they signed this petition, there was a very good chance that their businesses would be bombed, that they would certainly be boycotted, that their children might be harassed. Is there no First Amendment right in protecting those people?”

McKenna said the Supreme Court in January, in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission, had already allowed for case-by-case exceptions to be made concerning the disclosures of campaign contributors. The decision said the contributors would have to show a “reasonable probability” that disclosure of their names “would subject them to threats, harassment, or reprisals from either government officials or private parties.”

But McKenna added that, in Massachusetts, Florida, and Arkansas—three other states with public disclosure laws where gay-related ballot measures have come up—“no evidence has been provided that is in the record that anyone who signed any of these petitions in those three States was subjected to harassment.”

Justice Alito wanted to know how a person who might want to sign a petition proves there’s a sufficient threat of harassment before signing the petition. McKenna suggested it would be up to a petition’s sponsor to seek court approval to seal the records ahead of time.

That is what Protect Marriage did in Washington State, but its claim that its supporters were vulnerable to significant threats was not before the Supreme Court Wednesday—only its claim that the state public disclosure law was, in and of itself, unconstitutional.

Chief Justice Roberts asked McKenna whether he thought the court should grant a stay in this case to allow Protect Marriage to pursue an “as applied” challenge. McKenna said yes and noted that the petition forms are still sealed under the original federal district court ruling.

That, of course, means there’s a likelihood the Supreme Court will send this specific —over Referendum 71 petitions—back to the lower courts to enable Protect Marriage to challenge disclosure of its petitions under an “as-applied” basis.

But the potency of that specific challenge has diminished: Voters in 2008 rejected Referendum 71 and the domestic partnership law took effect last May.

To me this is a legal no-brainer. Why are we even having this conversation when the issue seems rather well established? This is second year Con Law stuff. I hardly think cowards and bigots can hide behind the ‘Right of Privacy’ when they publically “inject themselves into a controversy” on “matters of public interest” in order “to effect the outcome.” (See Gertz, Sullivan & Time) When you write a check or sign a petition to deny others their rights, those are not a private acts but very public ones, and it is axiomatic that there is ‘no right of privacy in a public place.’