June 26: An historic date marking victories that almost didn’t happen

June 26 is the most historic date on the LGBT civil rights movement’s calendar. It is the day in 2003 when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that states could not enforce laws prohibiting same-sex adults from having intimate relations. It is the day in 2013 when a Supreme Court procedural ruling enabled same-sex couples to marry in California. And it is the day in 2013 when the Supreme Court ruled that the federal government could not deny married same-sex couples the same benefits it provides to married male-female couples.

While the decision that allowed couples in California to marry provided important momentum to the marriage equality movement, the decisions in the 2003 Lawrence v. Texas and 2013 U.S. v. Windsor cases are undeniably the most important Supreme Court decisions ever issued on LGBT-related matters. Lawrence brought a crashing end to the longstanding presumption by society and the law that gays were “deviate” and should be singled out for disfavor.

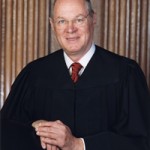

“When homosexual conduct is made criminal by the law of the State, that declaration in and of itself is an invitation to subject homosexual persons to discrimination both in the public and in the private spheres,” wrote Justice Anthony Kennedy for the 6 to 3 majority in Lawrence.

“…The State cannot demean their existence or control their destiny by making their private sexual conduct a crime. Their right to liberty under the Due Process Clause gives them the full right to engage in their conduct without intervention of the government.”

And it was Justice Kennedy who wrote the 5 to 4 majority decision in Windsor last year, striking the key provision of the federal Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA) that barred every federal entity from treating married same-sex couples the same as married heterosexual couples for the purpose of any federal benefit.

“The Constitution’s guarantee of equality ‘must at the very least mean that a bare congressional desire to harm a politically unpopular group cannot’ justify disparate treatment of that group,” wrote Kennedy in Windsor. “….DOMA’s unusual deviation from the usual tradition of recognizing and accepting state definitions of marriage here operates to deprive same-sex couples of the benefits and responsibilities that come with the federal recognition of their marriages. This is strong evidence of a law having the purpose and effect of disapproval of that class. The avowed purpose and practical effect of the law here in question are to impose a disadvantage, a separate status, and so a stigma upon all who enter into same-sex marriages made lawful by the unquestioned authority of the States.”

“….DOMA undermines both the public and private significance of state-sanctioned same-sex marriages; for it tells those couples, and all the world, that their otherwise valid marriages are unworthy of federal recognition,” wrote Kennedy. “This places same-sex couples in an unstable position of being in a second-tier marriage. The differentiation demeans the couple, whose moral and sexual choices the Constitution protects…. And it humiliates tens of thousands of children now being raised by same-sex couples. The law in question makes it even more difficult for the children to understand the integrity and closeness of their own family and its concord with other families in their community and in their daily lives.”

Kennedy’s words in both Lawrence and Windsor have been repeated in numerous court decisions since. And the powerful influence of words and decisions has almost obscured the fact that they were narrow victories.

In Lawrence, Kennedy wrote for just five of the six justices who considered sodomy laws to be unconstitutional; while Justice Sandra Day O’Connor provided a sixth vote in concurrence with the judgment, she did not join Kennedy’s opinion to the extent that it overruled the 1986 decision in Bowers v. Hardwick (which had upheld state sodomy laws). O’Connor said she would simply strike Texas’ law on equal protection grounds. (“Moral disapproval of this group, like a bare desire to harm the group, is an interest that is insufficient to satisfy rational basis review under the Equal Protection Clause.”)

In Windsor, Kennedy wrote for just five justices. One of those five, Elena Kagan, had been on the bench for only two and a half years and apparently had to recuse herself from a similar DOMA challenge that had reached the high court sooner because she likely discussed it while serving as Solicitor General. If the court had taken that first case, Gill v. Office of Personnel Management, the court likely would have rendered a tie vote and DOMA would still be in effect in most states.

Often forgotten, too, is the enormous influence the sitting president had on the impact of each decision.

The administration of President George W. Bush took no action in 2003 to see that the Lawrence decision was quickly and thoroughly respected by various federal programs, such as the military’s “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” law banning openly gay servicemembers. It continued enforcing the ban that had been approved by a Congress that pointed to sodomy laws to justify its hostile treatment of gays. Bush said nothing about the Lawrence decision and the White House press secretary brushed it off as a “state matter.” Then, in 2004, Bush spoke in support of a Congressional bill that sought to ban marriage for same-sex couples.

In contrast, President Obama spoke out quickly in support of the Supreme Court’s decision in Windsor and ordered his administration “to review all relevant federal statutes to ensure this decision, including its implications for Federal benefits and obligations, is implemented swiftly and smoothly.”

Legal activists responded differently following both decisions, too. LGBT legal activists were still wary of mounting lawsuits that would wind up in front of the Supreme Court. Even as late as 2009, they thought it was “too early” to put another issue to a vote at the Supreme Court.

But following the Windsor decision last year, legal activists filed more than 70 lawsuits in short order, challenging state laws in 30 states that banned marriage for same-sex couples.

Prior to the Windsor decision, 12 states and the District of Columbia allowed same-sex couples to marry. One year later, 18 states and D.C. have marriage equality and another 14 states have had courts declare their bans on same-sex couples marrying unconstitutional.

Prior to the Windsor ruling, 18 percent of the U.S. population lived in states with marriage equality. Today, not counting Wisconsin or Pennsylvania (whose bans are still subject to appeal), 39 percent of the population lives in marriage equality states.

U.S. Deputy Assistant Attorney General Pam Karlan shared with DOJ Pride attendees earlier this month some of her memories of having clerked for Supreme Court Justice Harry Blackmun in 1986 when he authored the dissent to the court’s Bowers v. Hardwick decision, upholding state laws prohibiting private consensual sex between same-sex adults. Karlan said she suggested to Blackmun that the majority opinion was resting on “an unexamined assumption that gay people were different in a way that permitted denying them” the right to intimate relations. When Blackmun wrote his dissent, she said, he made a subtle change to her suggested language, saying the majority opinion was based “on the assumption that homosexuals are so different from other citizens….”

“In making those changes, Justice Blackmun was doing two things,” said Karlan. “First, he was emphasizing that gay people are citizens – that is, true members of our national community. But second, and just as importantly, he was rejecting the idea that there is an ‘us’ for straight people – and that gay people are somehow a ‘them.’ And he was laying the groundwork for an understanding that the central constitutional claim is not just one about liberty; it is about equality as well.”

Leave a Reply