Kennedy’s questions: Clouds linger over standing in DOMA and Prop 8

Now that legal activists and experts have had a chance to go back over the U.S. Supreme Court arguments in last week’s two big marriage equality cases, most are predicting victories but only incremental ones.

In the Proposition 8 case, it appears that most believe the court will find that Hollingsworth v. Perry was improperly appealed. If so, a lower court decision striking Proposition 8 will remain intact, and same-sex couples in California will be able to obtain marriage licenses within a few days.

In the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA) case, U.S. v. Windsor, it appears most believe that, if the court reaches the merits, a 5 to 4 vote will strike the law down. But there is less confidence with Windsor about whether the court will get that far; many are unsure there will be 5 to 4 to say the case was properly before the court.

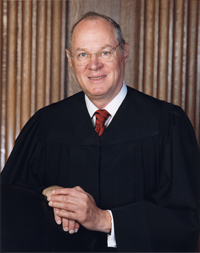

Much of the post-argument speculation is based on the general consensus that the court’s four more liberal justices – Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Stephen Breyer, Sonia Sotomayor, and Elena Kagan—will vote for marriage equality and that its four more conservative justices—Chief Justice John Roberts and Justices Antonin Scalia, Clarence Thomas, and Samuel Alito—will vote against. Justice Anthony Kennedy is considered the less predictable vote and one that could go either way to form a majority decision in either or both cases.

In the Proposition 8 argument, Kennedy asked three questions concerning legal standing and five concerning constitutional issues.

On legal standing, he sent mixed signals. He expressed discomfort with the idea that the governor or attorney general of California could seemingly “thwart the initiative process” by refusing to defend a voter-approved initiative all the way through the appellate process. He also rebuffed a statement by Chief Justice John Roberts—who said a state “can’t authorize anyone” to press an appeal. Kennedy said the Yes on 8 proponents were “different from saying any citizen.” Those two points seemed to support allowing Yes on 8 standing to appeal.

And yet, he acknowledged there is a “substantial question on standing.”

On the constitutional questions surrounding Proposition 8, Kennedy signaled five concerns. He underscored a question by Justice Ginsburg concerning whether Proposition 8 might be making a “gender-based classification,” adding that he sees it as a “difficult question” and one he has “been trying to wrestle with.” He challenged Cooper on whether Yes on 8 was “conceding” that allowing same-sex couples to marry posed “no harm or denigration to traditional opposite-sex marriage couples.” He voiced his own concern about the “immediate legal injury” Proposition 8 pressed on the 40,000 children of same-sex couples in California. (Cooper sought to deflect that concern by saying there was no data to indicate that marriage had any greater benefit for the children of same-sex parents than did domestic partnerships.)

But Kennedy also expressed his discomfort with the case dragging the court into “uncharted waters,” given the relative newness of families headed by same-sex couples. And he declared the Ninth Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals panel’s narrow ruling to be “very odd.” That latter declaration seemed odd itself, given that many the Ninth Circuit decision was based largely on a decision Kennedy wrote, in the 1996 Romer v. Evans decision.

Legal experts posting at scotus.com have identified at least seven potential outcomes in the Perry case, all of which would lead to same-sex couples being able to obtain marriage licenses again in California. One potential a ruling would require eight other states to allow same-sex couples to marry, and a long-shot possibility is that a ruling could require that bans in all states are unconstitutional. But with one exception (the Michigan attorney general), no one is predicting that the court will rule that Proposition 8 is a constitutionally valid measure.

University of California law dean Erwin Chermerinsky points out that there are two ways the Supreme Court could avoid ruling on the constitutionality of Proposition 8 in Hollingsworth v. Perry.

First, the court could decide that the appeal was “improvidently granted” review by the Supreme Court. That would leave the Ninth Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals ruling intact and gay couples could begin marrying again in California within days.

Second, it could decide that the Yes on 8 coalition had no legal standing to appeal to the Ninth Circuit; that would leave the federal district court’s broader ruling in effect. Gay couples could begin marrying again in California within days.

DOMA and consequences

Even though most legal experts say they believe Kennedy will likely provide the needed fifth vote to overcome the procedural obstacles in the DOMA case, he voiced twice as many questions on those issues as he did during the Proposition 8 case.

During oral argument in Windsor on March 27, he raised six questions over matters pertaining to the legal standing of the Bipartisan Legal Advisory Group (BLAG) and the jurisdiction of the Supreme Court in the matter.

Kennedy questioned whether BLAG, representing Republican House leadership on appeal, had standing. If just one chamber of Congress could assert standing, said Kennedy, then the other chamber (in this case, the Senate) could also assert standing “to take the other side of this case.”

Kennedy, like the more conservative justices on the court, said he found it “very troubling” that the president would continue to enforce a law that he considers unconstitutional. That appears to be a straw man argument, as it seems unlikely the court would concede its power of judicial review to the executive branch. But it follows in a line of questions about whether the U.S. government had any need to appeal the Second Circuit decision –that DOMA is unconstitutional. To have an appeal properly before the court, the appealing party must show it is injured by the decision and that there is adversity between the party and the decision. In other words, a party who wins a court decision below has no need to appeal it. And the Obama administration agrees that DOMA is unconstitutional.

Kennedy did, however, say it “seems” to him “there’s an injury here.” Justice Kagan identified the injury as a loss of the $363,000 plaintiff Edith Windsor paid to the government in estate taxes after her spouse died.

“If the Court dismisses Windsor on standing grounds, it is harder to know exactly what that will mean,” said Chermerinsky, in his March 28 essay at scotusblog.com.

“Ms. Windsor will prevail and not have to pay the estate tax owed after her spouse’s death,” said Chermerinsky. “But this would not strike down Section 3 of the Defense of Marriage Act. All other same-sex married couples seeking benefits under federal law would need to bring an action. President Obama, however, could cure this by changing his policy that the federal government will enforce, but not defend, DOMA. He could, and should, issue an executive order that DOMA is unconstitutional and the executive branch may not and will not enforce it.”

During oral argument on the DOMA case, Kennedy posed seven questions concerning the constitutionality of the law, five of them to BLAG attorney Paul Clement. Kennedy seemed to accept that the federal government might have occasional need to set a federal standard regarding marriage (for instance, to prevent couples from divorcing at the end of every tax year to reduce their tax bite). But he seemed uneasy with BLAG’s argument that “uniformity” was the overriding need for a definition of marriage that would exclude one group of married couples in more than 1,100 federal laws and regulations.

“When it has 1,100 laws, which in our society means that the federal government is intertwined with the citizens’ day-to-day life, you are at real risk of running in conflict with what has always been thought to be the essence of the state police power, which is to regulate marriage, divorce, and custody,” said Kennedy.

“It’s not really uniformity,” he added later, “because it regulates only one aspect of marriage.” And DOMA doesn’t, as Clement suggested, help the states, said Kennedy, because it contradicts states that have decided marriage for same-sex couples should be treated the same as marriage for male-female couples.

“We’re helping the states if they do what we want them to,” quipped Kennedy. And that, he said, is “not consistent with the historic commitment” of having states regulating marriage and the rights of children.

Kennedy shot down Clement’s claim that Congress, in passing DOMA, was “trying to promote democratic self-governance,” noting that DOMA “applies to states where the voters” have chosen marriage equality. And that, said Kennedy, is “a DOMA problem.”

Kennedy resisted efforts to consider the DOMA problem asserted by Solicitor General Donald Verrilli and Windsor attorney Roberta Kaplan –that DOMA violates the equal protection clause of the constitution.

Harvard law professor Laurence Tribe, who argued against sodomy laws in the Bowers v. Hardwick case in 1986, said, “I am cautiously optimistic that a majority of the justices will reach the merits in the Windsor case and will strike down Section 3 of DOMA, with the four more liberal justices relying principally on an equal protection analysis and with Justice Kennedy relying principally on federalism principles.”

So, if the court does reach the constitutional merits of DOMA, it appears a 5 to 4 majority will find DOMA unconstitutional but that only four of those five will say it also violates equal protection. That could mean Kennedy would be the likely author—for the third time since the 1996 Romer decision—to write a major pro-gay decision for the Supreme Court.

When might all the possible outcomes be known?

Even while predicting an outcome, nearly every Supreme Court watcher will acknowledge that outcomes are hard to predict when based on oral argument questions asked by the justices.

If the court finds a problem with legal standing or jurisdiction on either of these cases, it will likely issue that decision in the near future. Discussions of legal standing do not generally require a great deal of rumination.

If it decides on the merits, the decision or decisions will most likely come out—as they have with past major gay-related opinions—in the final week of the session—the last week in June.

It would be considerate of our constitution if at least one of the nine addressed the concept that our constitution prevents us from voting away the rights of others!