Prop 8 arguments roller coaster on standing and merits of marriage ban

The U.S. Supreme Court took the marriage equality issue on a roller coaster ride Tuesday as it heard almost 90 minutes of argument in the case testing the constitutionality of California’s ban on same-sex marriage.

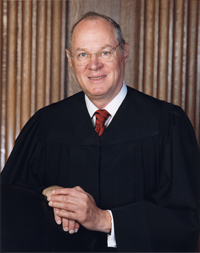

For supporters, the highs included Justice Sonia Sotomayor asking whether there was any other context other than marriage where there would be a rational basis reason for using sexual orientation as a factor in denying rights to gay people rights, to which Yes on 8 attorney Charles Cooper conceded “I do not have anything to offer.” And they included Justice Anthony Kennedy commenting on the importance of considering the “immediate legal injury” that 40,000 children in California suffer because their same-sex parents are not allowed to marry.

The lows included the considerable time justices spent wrangling over whether the Yes on 8 supporters of Proposition 8, California’s ban on same-sex marriage, have proper legal standing to appeal the case. It included Chief Justice John Roberts saying the debate was “just about the label” marriage. And it included Justice Antonin Scalia repeatedly interrupting marriage equality attorney Ted Olson demanding that he identify “when did it become unconstitutional to exclude homosexuals” from marriage. But none of the three attorneys had an easy day.

Chief Justice Roberts tackled Solicitor General Donald Verrilli over his brief to the court, saying it was “inconsistent.” Roberts noted that Verrilli was arguing that the children of same-sex couples do as well as the children of male-female couples, while also arguing that Proposition 8 harms the children of same-sex couples.

“Which is it?” asked Roberts.

Cooper stumbled, too, when Justices Stephen Breyer and Elena Kagan challenged his argument that marriage is all about regulating procreation. If so, asked Breyer, why does California allow sterile male-female couples to marry? If so, asked Kagan, why allow people over 55 to get married. (Cooper, to much laughter in the courtroom, offered that it was “very rare that both parties in such marriages are infertile.”)

Olson, lead attorney with David Boies of the American Foundation for Equal Rights team representing two same-sex couples, got into the most prolonged and exchange of the session when Justice Scalia demanded to know “when” it became unconstitutional to exclude gays from marriage. Scalia repeatedly insisted Olson identify a “specific date in time.” Olson tried several times to answer the question and eventually shot back, “you’ve never required that before.”

Gay legal activists seemed impressed with the overall discussion and most enthusiastic about Justice Sotomayor’s pointed question to Cooper, concerning other areas where gays could be excluded from rights.

“It was basically asking him whether it’s permissible to treat gay people differently from everyone else in anything else other than marriage,” said Bonauto. “And [Cooper] said, ‘I can’t think of anything, no.’

“I thought that was extremely important in terms of acknowledging equal treatment,” said Bonauto. “I thought that was critical.”

Jon Davidson, legal director for Lambda Legal Defense, said a high point for him was Kennedy’s remark about the “legal impact” on children of same-sex couples.

“I was really encouraged that he was thinking about the children of same-sex marriage. That is a very good sign.”

Kate Kendell, executive director of the National Center for Lesbian Rights, said she was a little surprised by the “rather heated exchange” between Scalia and Olson, over when it became unconstitutional to exclude gays from the right to marry.

“What Ted Olson should have said is, ‘It’s always been a violation of the constitution but, like in many of the other cases [involving rights withheld from other groups], it took a while for us to recognize that this right always existed for these people that we treated differently in the past.”

“I doubt that if any other lawyer had been up there it would have been as heated,” said Kendell, who said the exchange was like “two old friends” having a debate.

But each of the legal activists cautioned that it’s important not to read too much into what the justices said or asked.

“We all know you can’t tell from argument how it’s going to go,” said Evan Wolfson, head of the national Freedom to Marry group. “The argument showed they’re wrestling with a lot of these big questions. I think standing is very much on their mind—very much a live part of the case. But they also were really grappling with the merits.”

Though none mentioned it, it must have been somewhat worrisome for marriage equality supporters to hear Justice Kennedy say, “the problem with this case” is that it is asking the court to “go into uncharted waters.” That mantra was repeated by several other justices during the argument in the case, Hollingsworth v. Perry. Justice Samuel Alito echoed it when he told Solicitor General Donald Verrilli that marriage for same-sex couples is a “very new” phenomenon, newer than cell phones.

“You want us to step into” this debate, he said, when “we don’t have the ability to see into the future. Why not leave it to the people?”

But hearing it from Kennedy was even more worrisome because he is considered the most likely fifth vote to provide a majority on one side or the other. Kennedy wrote the opinion in the 1996 Romer v. Evans decision striking an anti-gay initiative in Colorado and in the 2003 Lawrence v. Texas decision striking down sodomy laws. Both sides of the Proposition 8 case consider him the key vote to sway in order to consolidate a five-vote majority.

But Kennedy has been listing toward the conservative wing of the court recently, leading its dissent against President Obama’s Affordable Care Act and leading its majority ruling to allow corporations to contribute without limits to political campaign activities. And in a speech in Sacramento March 6, he worried many marriage equality supporters when he told reporters he thinks it is a “serious problem” that the Supreme Court is being asked to settle controversial issues facing a democracy.

The Hollingsworth v. Perry case is testing the constitutionality of California’s voter-approved ban on same-sex marriage. Voters approved Proposition 8 in November 2008, just six months after a California Supreme Court ruling found that the state constitution required that same-sex couples be able to obtain marriage licenses the same as male-female couples do.

The American Foundation for Equal Rights organized the original lawsuit in federal district court in San Francisco in January 2010, initially over the objections of LGBT legal activists and groups. But the groups came onboard quickly and U.S. District Court Chief Judge Vaughn Walker (who came out as gay after retirement in 2011) issued a decision in August 2010, saying Proposition 8 violated the federal equal protection and due process clauses, that there was no rational basis for limiting the designation of marriage to straight couples, and that there was no compelling reason for the state to deny same-sex couples the fundamental right to marry.

Then California Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger and Attorney General Jerry Brown declined to appeal Walker’s ruling, but Yes on 8 was granted permission to do so. A Ninth Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals panel upheld Walker’s decision but on much more narrow grounds. It said the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1996 ruling in Romer precluded voters from withdrawing the right to marry from same-sex couples in California. But the Supreme Court asked for arguments on the broader question of whether Proposition 8 violates the constitutional right to equal protection. It also asked whether Yes on 8 has proper legal standing to appeal the case after California elected officials decided not to.

As expected, there was considerable attention on the cases from the mainstream news organizations leading up to the arguments and very heavy media coverage of the argument Tuesday. Many nationally televised political talk shows spent time with commentators speculating whether the justices might be influenced by the latest polls showing growing popular support for marriage equality.

A number of news and commentary sites reported that Chief Justice John Roberts’ openly gay cousin –48-year-old Jean Podrasky of San Francisco— and her partner Grace Fasano would be in the courtroom as the Chief Justice’s guest. The Los Angeles Times quoted her as saying that, “He is a good man. I believe he sees where the tide is going. I do trust him. I absolutely trust that he will go in a good direction.” She acknowledged that, while Roberts knows she’s gay, she does not have any personal knowledge his views on the marriage issue.

People began standing in line for public seats on Thursday afternoon, five days before the Proposition 8 argument and in weather that was in the low thirties with rain and snow. On Monday afternoon, most were huddled under large blue tarps to fend off a wet snowfall. None of the dozen or so whom this reporter talked to acknowledged being professional “line-sitters,” though one small group did say they were holding places in line for friends from California. Surprisingly few said they were gay.

Three young men relatively near the front of the line were with the Family Research Council, which opposes same-sex marriage.

Abigail Cromwell, a former criminal prosecutor from Cambridge, flew in Monday morning to see if she could get a seat. She supports marriage equality.

But the reasons each gave for trying to get into Tuesday’s argument was similar: history.

“This is the most important case of our generation,” said Cromwell.

“This is the civil rights issue of our time,” said a man in his fifties or sixties at the very front of the line. Rick declined to give his last name.

On the other end of the National Mall from the Supreme Court on Tuesday, the National Organization for Marriage held a rally of opponents of allowing same-sex couples to marry. The rally was broadcast live by C-SPAN.

The Proposition 8 case was the first of two historic oral arguments before the Supreme Court this week. On Wednesday, the court is set to hear arguments in U.S. v. Windsor, testing the constitutionality of the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA).

Leave a Reply